Intercultural communication (Friendly vegetables by Jim Morris - part 2)

Author

Jim Morris

Intercultural communication (Friendly vegetables by Jim Morris - part 2)

We cannot not communicate. Even when we are silent we are communicating. “Communication is the accurate transfer of ideas, feelings, thoughts, information and / or emotions, from the mind of one individual to another without loss or distortion.”

In this section we will cover four important elements of communicating plus gain insight on two key cultural differences (individualism versus collectivism and perception on time) that will help strengthen the IRC competence of Intercultural Communication.

Face

Body language

Language

Context

When communicating you have a “sender” and “receiver”. As sender, the language you speak, the words and gestures you use, can easily be interpreted by the receiver in a very different way to what you intended. Always find a moment to check that the receiver has understood you correctly. If you are the receiver take time to check and summarize what the other person is telling you. We should steer clear of the pitfall of assuming that what we do and say mean the same thing, even if the spoken language is common to both parties.

Look at the communication model below which shows the process of sending and receiving a message. With so many steps it is clear that messages can get distorted along the way if we are not fully focused on our communication. People from the same culture mis-communicate, so when the extra element of culture is added to the process it is easy to understand why people struggle to communicate effectively.

Face

Face versus the truth

The scene in the cartoon below takes place in Hong Kong. Why do you think the woman in the queue is telling the western man that he is rude?

Cartoon: Feign, 1987 – Fong’s Aieeyaa, Not Again, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Standard, reproduced in Smith and Bond (1998)

The explanation is twofold

You might have come up with answers such as:

Due to the fact that the man is pointing

Due to the fact that the man is tapping the boy on the shoulder.

The two explanations are in fact:

The western man considers ‘jumping a queue’ wrong: in his culture ‘it is good to queue, bad to jump a queue’. He also considers it appropriate to confront someone with this in public, and believes that he is doing this in a polite manner.

Queuing, however is not given the same level of importance in Asia, so the woman thinks the man’s behavior is rude. More importantly, many Asians prefer to ignore and avoid conflict because their aim is to reduce animosity and ensure that people do not lose face, especially in public.

Balancing face and truth

In our communication with other people we like to balance the aspect of politeness and saving face with the facts and the truth. Which way the scale tips (towards face or truth) determines our choices.

If face “wins”:

‘Loss of face’ to be avoided, especially in public: politeness

Use of indirect language to save face

Not saying ‘No’, and different meaning of ‘Yes’: often used to save face of the person asking the question

If the truth “wins”:

Telling the truth is very important: the feeling of ‘loss of face’ is not so strong

Use of direct language: important to tell the facts and give constructive feedback

Saying ‘No’ easily and not feeling offended if people answer your question with ‘No’. A ‘Yes’ always means a ‘Yes’

About the author: Jim Morris is a senior facilitator and project manager for Schouten Global. He lives and breathes culture: English by nationality, he lives in the Netherlands and works all over the world facilitating professional learning and development. His latest book The Eight Great Beacons of Cultural Awareness (is a practical guide and will strengthen your cultural awareness) is available as e-book here.

People’s face in culture

Face is concerned with people’s sense of worth, dignity and identity. It is associated with issues such as respect, honor, status, reputation and competence. Face is a universal phenomenon. However, culture can affect the sensitivity of ‘face’ and strategies to manage ‘face’ - both in public and in private.

Loss of face is to be avoided at all cost in many countries, especially in public. In some countries preventing your manager from losing face is also very important. The use of indirect language is helpful in this respect. Avoiding saying ‘No’, and attributing a different meaning to ‘Yes’ is often used to save face of the person asking the question.

Similar situations can often occur in business when dealing with cultures which put face before truth. When a manager explains a task to an employee the manager may be told they are understood by their employee not be-cause the employee has actually understood but because the employee would not want to suggest that the manager had not explained it well.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: Tips for communicating to avoid loss of face: • Be indirect: use veiled comments and hints; tell hypothetical stories about yourself • Use an intermediary • Give feedback to an individual in a group, without naming the person • Avoid asking Yes/No questions: instead ask open, probing questions • Do not take ‘Yes’ for a confirmation or promise: it can mean ‘I have heard you’ • Give people time to prepare input for meetings, preferably in small groups • Do not expect immediate decisions or agreement

His face was as red as a beetroot The “terrible curse of English good manners”

A true story from a BBC correspondent when George Bush was president of America:

We are not close, Mr. Bush and I, because as you know he is busy and when he does give interviews they tend, understandably, to be with American networks. Occasionally he is available for the British press. Sadly, my friend Tim Reid, who writes for the London Times has not been fortunate to interview the then president of America. I wonder if that has anything to do with the following misunderstanding. At a previous Christmas party, Tim was introduced to Mr. Bush as "Tim Reid from the Times". Unfortunately, the president had recently been interviewed by one of Tim's colleagues, not by Tim, but hearing the words "The Times" Mr. Bush said, not unreasonably, "Hey Tim - didn't we meet just a few days ago?".

As Tim describes it, the terrible curse of English good manners kicked in and he felt unable to contradict the commander-in-chief. Instead he heard himself mutter, "Umm, well, yes Mr. President we might have met..."."Might have met!" Mr. Bush looked surprised, and turning to Tim's wife, raised an eyebrow and said, "You'd have thought he'd have remembered!"America's 43rd president has suffered all manner of indignities in recent years; but surely none so searing...

In the above story there is a clear example of face versus truth resulting in indirect use of language and not daring to say no.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: Remember what you used to think was face-to-face communication could in fact in cross-cultural encounters be face-to-truth or truth-to-face communication. Think about your own culture. Does the scale tip in favour of face or truth for you?

Body language

We interpret body language unconsciously. It makes up a very important part of understanding a message. Our non-verbal “Outside behavior” (what others see) makes up two thirds of how we communicate. The verbal (actual words we speak) communication makes up just one third.

"I say toh-mah-toh, you say toh-may-toh”

In the famous song “Let’s call the whole thing off” by George Gershwin, the relationship between two people is threatened because they do not understand each other’s regional dialects. Not willing to invest in understanding the other person, they suggest that they “call the whole thing off”. An opportunity for cultural enlightenment is lost and the two people create an even greater distance between themselves.

Similarly when people see a tomato some would say that it is a vegetable others insist it is a fruit. Understanding another culture is understanding that things can be seen differently. In another culture often what you see or hear may not be what you think you see or hear.

In today’s world, the internet, television and travel have helped carry non- verbal signs (and words) across national boundaries, so that people are tempted to think that gestures and expressions mean the same everywhere. Not so. You may see the same signs in other places, but they do not necessarily mean the same thing as they do in your culture. Here is one example of one hand gesture which means something completely different in the three countries/cultures mentioned.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: If you are struggling to understand somebody from another culture don’t “call the whole thing off”. Instead remember these three words: Learn, Adapt, Respect.

Thumbs up if you disagree

A thumbs up signal has become a metaphor in the English language: "My boss gave my proposal the thumbs up" means that the boss approved the proposal, regardless of whether the gesture was made — indeed, the gesture itself is unlikely in a formal business setting.

So should we conclude then that this is a common gesture of approval? No we should not! When you consider the thumbs-up signal, what do you think this gesture means? Give yourself a few moments to consider your answer before reading on. Here are just some examples of what this gesture can mean in different cultures.

"Thumbs up" traditionally translates as the most offensive of gesticular insults in some Middle Eastern countries.

The sign has a similar insulting meaning in parts of West Africa, South America, Iran, and Iraq.

In Bangladesh and Thailand it is traditionally an obscene gesture, equivalent to the use of the middle finger in the western world.

In Italy, in the right context, it can simply indicate the number one.

In the UK a single-handed thumbs-up sign can be used as a greeting or farewell gesture (often used as a replacement for a more traditional "wave" goodbye).

Tip from Carl the Carrot: We cannot be expected to understand and learn all the rules in non- verbal communication for all cultures. What we can do is show cultural sensitivity. Understand that there will be multiple meanings for gestures and be-come more conscious of not jumping to conclusions. Ask your friends what the thumbs-up gesture means to them.

Language

Tales or tails of the “joy” of culture.

Speech is part of culture. A culture develops a spoken language which ex-presses the things that culture believes in, its ideas and the objects with which it is familiar.

This is why translating from one language to another is so difficult. The French, for example talk about “ennui” which would be translated in English as “boredom”. However, this is not exactly what it means to the French, who would also consider it to cover a kind of tiredness of the spirit.

The Eskimos have many different words for different kinds of snow. Their culture needs this in a land where their lifestyle and survival depends on different kinds of snow. By the way the above picture is another kind of snow… the snow pea!

Eskimos may have many words for snow but they have no real word for joy. Bishop John Sperry, a retired Anglican Bishop of the Arctic, had been a missionary bishop in the vast Yukon Territory, where there was no Inuit (Eskimo) translation of the Bible. So, he set about producing one, but fairly quickly came to a sudden halt. In the Inuit language there is no word for joy, just images and metaphors. When the translators came to the resurrection story (John 20:20) they had to find a word to express joy, and the closest metaphor to what joy meant in the Inuit culture was “wagging the tail”. That explains why in Inuit, John 20:20 became, “When the disciples saw the Lord they wagged their tails”.

So we can conclude that culture affects how we communicate, and as part of that the spoken language certainly helps define the culture. Therefore, what we mean when we say something depends partly on our culture. For example, an Indian being interviewed for a job in England may believe it important to talk at length about his or her qualifications. This is because their culture is a matter of status and sound argument, stressing good qualifications at an interview. The English interviewer, however, could well see this as rather irrelevant and a little boastful.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: What we say is not always what we think we mean. “Let my words - like vegetables - be tender and sweet, for tomorrow I may have to eat them.” - author unknown.

Context

Low-context cultures versus high-context cultures

When somebody asks you to explain something, do you give a brief outline or do you go into great detail? How you answer will give an insight into whether you are from a low- or high-context culture. Context refers to the amount of background information that is needed to interpret what people say.

It consists of the amount of innate and largely unconscious understanding a person can be expected to bring to a particular communication setting. It is also related to the way information is dealt with and ordered, and the amount of contextual information required to understand a message (see Hall).

Tip from Carl the Carrot:When communicating with someone from a high-context culture, add more context and start with explaining before describing the essence by explaining this.

Are you an individualist or a collectivist?

When working in a group, people from individualist cultures tend to be focused more on the task, the ‘task prevails over the relationship’. A key difference is that people from collectivist cultures tend to be more focused on the persons, or ‘relationship prevails over task’. There is a clear link to a country’s GDP: people in rich countries are less dependent on external or family support and thus tend to be more individualistic.

In-group versus out-group

Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family. Collectivism as its opposite pertains to societies in which people are integrated from birth onwards into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

The following definitions of in-groups and out-groups were formulated by Triandis, 1995:

In-groups: groups of individuals about whose welfare a person is concerned, with whom that person is willing to co-operate without demanding equitable returns and separation which leads to anxiety;

Out-groups: groups with which one has something to divide perhaps unequally, or are harmful in some way, groups that disagree on valued attributes, or groups with which one is in conflict.

In general, in collectivist cultures one finds a sharp distinction between what people consider to be in-groups and out-groups, and thus also differences in the behavior towards members of in-groups (loyalty, support, understanding) versus out-groups (lack of interest, competitiveness, antagonism). This feature is less distinct in individualist countries. In collectivist cultures once one is a member of an in-group this is often for the long- term.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: How would you describe yourself when completing the sentence: “I am …” Where you place yourself in relation to other people will give you an indication of whether you are more of an individualist of collectivist. For example “I am tall” or “I am dark haired” is more individual whereas “I am a father” or “I am a member of the local football team” is more collective.

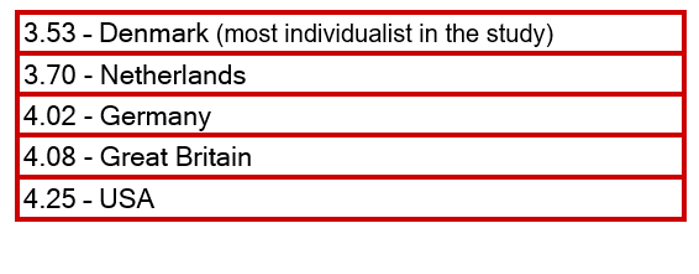

Below are some examples of the scores which the Globe study (House, 2004) indicates for individualism and collectivism in a country. The first examples are individualistic cultures.

If you are working with an individualistic culture then you should remember the following beliefs such a culture indicates:

Management is management of individuals

Task prevails over relationship

Hiring and promotion decisions are (supposed to be) based on skills and rules only

The employer-employee relationship is a contract supposed to be based on mutual advantage Next are some examples of collectivist cultures.

If you are working with a collective culture you should remember the follow-ing beliefs such a culture has:

Management is management of groups

Relationship prevails over task

Hiring and promotion decisions take employees’ social networks into account

The employer-employee relationship is perceived in moral terms, like a family link

Tip from Carl the Carrot: Consider the words of Nandan Nilekani, CEO, President and Managing Di-rector, Infosys Technologies Ltd, India: “I would advise all young men and women to recognize, learn and assimilate changes and have the ability to work as part of a team, subsuming individual glory to team achievement.”

It takes two to tango

In the British dictionary of slang the word “swede” (see photo of the vegetable swede) refers to a less intelligent person and is often used when some-one does something which is not clever. It can also refer to the size of someone’s head, especially a big head leading to remarks such as “look at the size of his swede”. In the example below we do not look at the vegetable but rather the Swedes as a culture. Certainly they are far from being stupid or dumb in the example given!

The following is a story of a Dutch company and a Swedish company (both individualistic cultures) who were in competition to secure a valuable contract in Brazil. Both companies had been invited to Brazil to present their tender bids.

The Dutch made a first-class presentation. It really was tiptop and would create huge savings for the Brazilians. The meeting was on a Friday. The Dutch flew in to Rio de Janeiro late on the Thursday night and went straight to their hotel rooms so that they would be fresh for their presentation. The following morning their presentation was flawless, dynamic and very professionally made. Convinced they had secured the deal they thanked their hosts and flew out that afternoon back to Amsterdam.

The Swedes had arrived on the Tuesday. On the Wednesday they had lunched with the team leaders and on Thursday acquainted themselves with the staff at the office and had dinner with senior management the same evening. They had with them a reasonable proposal for the business. A bit rough around the edges perhaps but essentially a good proposal. It would not save the Brazilians as much money as the Dutch document. Their presentation on Friday morning was average. Solid and straightforward but nowhere near as dynamic as that of the Dutch. The Swedes explored Rio on Saturday before flying to Stockholm on Sunday.

Who got the business? It was the Swedes who were successful. Despite a mediocre presentation and proposal they had understood the value a collective culture like South America puts on relationship rather than the task. The Dutch may have had the better proposal on paper but they had failed to in-vest in the relationship with the Brazilians. As a collective culture the managers in Rio were looking for a strong relationship to give them the necessary feeling of trust needed to do business.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: Never assume that the rules in your culture will work in another culture.

Time

In the famous fairy tale, if Cinderella wasn’t home by midnight, she would turn into a pumpkin. The story dates back many years, even as far back as Greek and Roman times, so it is difficult to link it to one particular culture. However, its origin is more likely to have been a “monochronic” culture rather than a “polychronic” culture.

Cinderella would not have been under so much pressure to return by mid-night in a culture which considers time as the servant and not the master. Relationships (such as finding your Prince Charming) rather than how you actually manage your time would be much more important in a polychronic culture.

Listed below are perceptions of time from both monochronic and polychronic cultures in business.

Monochronic:

Time is money, a commodity

Time is sequential

You are judged by how well you control time

You cannot be trusted if you can’t manage your time

You are very punctual and focused

Time is fluid and flexible

Time is synchronic

Time is your servant, not your master

How you nurture relationships is more important than how you manage your time

You are flexible and good at multi-tasking Some examples of these cultures are, Mexico, India, Arab World, Italy, France, Africa.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: As one man from Senegal put it: “Africans have the time, Europeans have the watch.”

Fast food

…I’ll have a monochronic cheeseburger to go please.

The highest scoring monochronic country is the USA. (We would write Unit-ed States of America, but it just takes too much time!) Even with all its diversity the general trend is that scheduling, segmentation and promptness are all very important in America. Time is something tangible and valuable to Americans. No surprise, then, that restaurants like the one pictured below are welcomed in the USA. Look closely and you will see that ten-minute lunches are guaranteed.

Tip from Carl the Carrot: Do not try to judge someone on their use of time; you may end up judging their culture. Think about this when for example someone is late, or exactly on time. If someone is serving several customers at the same time or letting you wait. How does this make you feel?

Intercultural communication (Friendly vegetables by Jim Morris - part 2)

We cannot not communicate. Even when we are silent we are communicating. “Communication is the accurate transfer of ideas, feelings, thoughts, information and / or emotions, from the mind of one individual to another without loss or distortion.”

In this section we will cover four important elements of communicating plus gain insight on two key cultural differences (individualism versus collectivism and perception on time) that will help strengthen the IRC competence of Intercultural Communication.

When communicating you have a “sender” and “receiver”. As sender, the language you speak, the words and gestures you use, can easily be interpreted by the receiver in a very different way to what you intended. Always find a moment to check that the receiver has understood you correctly. If you are the receiver take time to check and summarize what the other person is telling you. We should steer clear of the pitfall of assuming that what we do and say mean the same thing, even if the spoken language is common to both parties.

Look at the communication model below which shows the process of sending and receiving a message. With so many steps it is clear that messages can get distorted along the way if we are not fully focused on our communication. People from the same culture mis-communicate, so when the extra element of culture is added to the process it is easy to understand why people struggle to communicate effectively.

Face

Face versus the truth

The scene in the cartoon below takes place in Hong Kong. Why do you think the woman in the queue is telling the western man that he is rude?

Cartoon: Feign, 1987 – Fong’s Aieeyaa, Not Again, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Standard, reproduced in Smith and Bond (1998)

The explanation is twofold

You might have come up with answers such as:

The two explanations are in fact:

Balancing face and truth

In our communication with other people we like to balance the aspect of politeness and saving face with the facts and the truth. Which way the scale tips (towards face or truth) determines our choices.

If face “wins”:

If the truth “wins”:

About the author: Jim Morris is a senior facilitator and project manager for Schouten Global. He lives and breathes culture: English by nationality, he lives in the Netherlands and works all over the world facilitating professional learning and development. His latest book The Eight Great Beacons of Cultural Awareness (is a practical guide and will strengthen your cultural awareness) is available as e-book here.

People’s face in culture

Face is concerned with people’s sense of worth, dignity and identity. It is associated with issues such as respect, honor, status, reputation and competence. Face is a universal phenomenon. However, culture can affect the sensitivity of ‘face’ and strategies to manage ‘face’ - both in public and in private.

Loss of face is to be avoided at all cost in many countries, especially in public. In some countries preventing your manager from losing face is also very important. The use of indirect language is helpful in this respect. Avoiding saying ‘No’, and attributing a different meaning to ‘Yes’ is often used to save face of the person asking the question.

Similar situations can often occur in business when dealing with cultures which put face before truth. When a manager explains a task to an employee the manager may be told they are understood by their employee not be-cause the employee has actually understood but because the employee would not want to suggest that the manager had not explained it well.

• Be indirect: use veiled comments and hints; tell hypothetical stories about yourself

• Use an intermediary • Give feedback to an individual in a group, without naming the person

• Avoid asking Yes/No questions: instead ask open, probing questions

• Do not take ‘Yes’ for a confirmation or promise: it can mean ‘I have heard you’

• Give people time to prepare input for meetings, preferably in small groups

• Do not expect immediate decisions or agreement

His face was as red as a beetroot

The “terrible curse of English good manners”

A true story from a BBC correspondent when George Bush was president of America:

We are not close, Mr. Bush and I, because as you know he is busy and when he does give interviews they tend, understandably, to be with American networks. Occasionally he is available for the British press. Sadly, my friend Tim Reid, who writes for the London Times has not been fortunate to interview the then president of America. I wonder if that has anything to do with the following misunderstanding. At a previous Christmas party, Tim was introduced to Mr. Bush as "Tim Reid from the Times". Unfortunately, the president had recently been interviewed by one of Tim's colleagues, not by Tim, but hearing the words "The Times" Mr. Bush said, not unreasonably, "Hey Tim - didn't we meet just a few days ago?".

As Tim describes it, the terrible curse of English good manners kicked in and he felt unable to contradict the commander-in-chief. Instead he heard himself mutter, "Umm, well, yes Mr. President we might have met..."."Might have met!" Mr. Bush looked surprised, and turning to Tim's wife, raised an eyebrow and said, "You'd have thought he'd have remembered!"America's 43rd president has suffered all manner of indignities in recent years; but surely none so searing...

In the above story there is a clear example of face versus truth resulting in indirect use of language and not daring to say no.

Body language

We interpret body language unconsciously. It makes up a very important part of understanding a message. Our non-verbal “Outside behavior” (what others see) makes up two thirds of how we communicate. The verbal (actual words we speak) communication makes up just one third.

"I say toh-mah-toh, you say toh-may-toh”

In the famous song “Let’s call the whole thing off” by George Gershwin, the relationship between two people is threatened because they do not understand each other’s regional dialects. Not willing to invest in understanding the other person, they suggest that they “call the whole thing off”. An opportunity for cultural enlightenment is lost and the two people create an even greater distance between themselves.

Similarly when people see a tomato some would say that it is a vegetable others insist it is a fruit. Understanding another culture is understanding that things can be seen differently. In another culture often what you see or hear may not be what you think you see or hear.

In today’s world, the internet, television and travel have helped carry non- verbal signs (and words) across national boundaries, so that people are tempted to think that gestures and expressions mean the same everywhere. Not so. You may see the same signs in other places, but they do not necessarily mean the same thing as they do in your culture. Here is one example of one hand gesture which means something completely different in the three countries/cultures mentioned.

Thumbs up if you disagree

A thumbs up signal has become a metaphor in the English language: "My boss gave my proposal the thumbs up" means that the boss approved the proposal, regardless of whether the gesture was made — indeed, the gesture itself is unlikely in a formal business setting.

So should we conclude then that this is a common gesture of approval? No we should not! When you consider the thumbs-up signal, what do you think this gesture means? Give yourself a few moments to consider your answer before reading on. Here are just some examples of what this gesture can mean in different cultures.

Language

Tales or tails of the “joy” of culture.

Speech is part of culture. A culture develops a spoken language which ex-presses the things that culture believes in, its ideas and the objects with which it is familiar.

This is why translating from one language to another is so difficult. The French, for example talk about “ennui” which would be translated in English as “boredom”. However, this is not exactly what it means to the French, who would also consider it to cover a kind of tiredness of the spirit.

The Eskimos have many different words for different kinds of snow. Their culture needs this in a land where their lifestyle and survival depends on different kinds of snow. By the way the above picture is another kind of snow… the snow pea!

Eskimos may have many words for snow but they have no real word for joy. Bishop John Sperry, a retired Anglican Bishop of the Arctic, had been a missionary bishop in the vast Yukon Territory, where there was no Inuit (Eskimo) translation of the Bible. So, he set about producing one, but fairly quickly came to a sudden halt. In the Inuit language there is no word for joy, just images and metaphors. When the translators came to the resurrection story (John 20:20) they had to find a word to express joy, and the closest metaphor to what joy meant in the Inuit culture was “wagging the tail”. That explains why in Inuit, John 20:20 became, “When the disciples saw the Lord they wagged their tails”.

So we can conclude that culture affects how we communicate, and as part of that the spoken language certainly helps define the culture. Therefore, what we mean when we say something depends partly on our culture. For example, an Indian being interviewed for a job in England may believe it important to talk at length about his or her qualifications. This is because their culture is a matter of status and sound argument, stressing good qualifications at an interview. The English interviewer, however, could well see this as rather irrelevant and a little boastful.

Context

Low-context cultures versus high-context cultures

When somebody asks you to explain something, do you give a brief outline or do you go into great detail? How you answer will give an insight into whether you are from a low- or high-context culture. Context refers to the amount of background information that is needed to interpret what people say.

It consists of the amount of innate and largely unconscious understanding a person can be expected to bring to a particular communication setting. It is also related to the way information is dealt with and ordered, and the amount of contextual information required to understand a message (see Hall).

Are you an individualist or a collectivist?

When working in a group, people from individualist cultures tend to be focused more on the task, the ‘task prevails over the relationship’. A key difference is that people from collectivist cultures tend to be more focused on the persons, or ‘relationship prevails over task’. There is a clear link to a country’s GDP: people in rich countries are less dependent on external or family support and thus tend to be more individualistic.

In-group versus out-group

Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family. Collectivism as its opposite pertains to societies in which people are integrated from birth onwards into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

The following definitions of in-groups and out-groups were formulated by Triandis, 1995:

In general, in collectivist cultures one finds a sharp distinction between what people consider to be in-groups and out-groups, and thus also differences in the behavior towards members of in-groups (loyalty, support, understanding) versus out-groups (lack of interest, competitiveness, antagonism). This feature is less distinct in individualist countries. In collectivist cultures once one is a member of an in-group this is often for the long- term.

Below are some examples of the scores which the Globe study (House, 2004) indicates for individualism and collectivism in a country. The first examples are individualistic cultures.

If you are working with an individualistic culture then you should remember the following beliefs such a culture indicates:

If you are working with a collective culture you should remember the follow-ing beliefs such a culture has:

It takes two to tango

In the British dictionary of slang the word “swede” (see photo of the vegetable swede) refers to a less intelligent person and is often used when some-one does something which is not clever. It can also refer to the size of someone’s head, especially a big head leading to remarks such as “look at the size of his swede”. In the example below we do not look at the vegetable but rather the Swedes as a culture. Certainly they are far from being stupid or dumb in the example given!

The following is a story of a Dutch company and a Swedish company (both individualistic cultures) who were in competition to secure a valuable contract in Brazil. Both companies had been invited to Brazil to present their tender bids.

The Dutch made a first-class presentation. It really was tiptop and would create huge savings for the Brazilians. The meeting was on a Friday. The Dutch flew in to Rio de Janeiro late on the Thursday night and went straight to their hotel rooms so that they would be fresh for their presentation. The following morning their presentation was flawless, dynamic and very professionally made. Convinced they had secured the deal they thanked their hosts and flew out that afternoon back to Amsterdam.

The Swedes had arrived on the Tuesday. On the Wednesday they had lunched with the team leaders and on Thursday acquainted themselves with the staff at the office and had dinner with senior management the same evening. They had with them a reasonable proposal for the business. A bit rough around the edges perhaps but essentially a good proposal. It would not save the Brazilians as much money as the Dutch document. Their presentation on Friday morning was average. Solid and straightforward but nowhere near as dynamic as that of the Dutch. The Swedes explored Rio on Saturday before flying to Stockholm on Sunday.

Who got the business? It was the Swedes who were successful. Despite a mediocre presentation and proposal they had understood the value a collective culture like South America puts on relationship rather than the task. The Dutch may have had the better proposal on paper but they had failed to in-vest in the relationship with the Brazilians. As a collective culture the managers in Rio were looking for a strong relationship to give them the necessary feeling of trust needed to do business.

Time

In the famous fairy tale, if Cinderella wasn’t home by midnight, she would turn into a pumpkin. The story dates back many years, even as far back as Greek and Roman times, so it is difficult to link it to one particular culture. However, its origin is more likely to have been a “monochronic” culture rather than a “polychronic” culture.

Cinderella would not have been under so much pressure to return by mid-night in a culture which considers time as the servant and not the master. Relationships (such as finding your Prince Charming) rather than how you actually manage your time would be much more important in a polychronic culture.

Listed below are perceptions of time from both monochronic and polychronic cultures in business.

Monochronic:

Fast food

…I’ll have a monochronic cheeseburger to go please.

The highest scoring monochronic country is the USA. (We would write Unit-ed States of America, but it just takes too much time!) Even with all its diversity the general trend is that scheduling, segmentation and promptness are all very important in America. Time is something tangible and valuable to Americans. No surprise, then, that restaurants like the one pictured below are welcomed in the USA. Look closely and you will see that ten-minute lunches are guaranteed.

This is chapter 2 from the book With friendly vegetables by Jim Morris. Read the next chapter here or download the book here.